The Strange Case of Two State Agencies’ Revolving Door Policies

The Strange Case of Two State Agencies’ Revolving Door Policies —

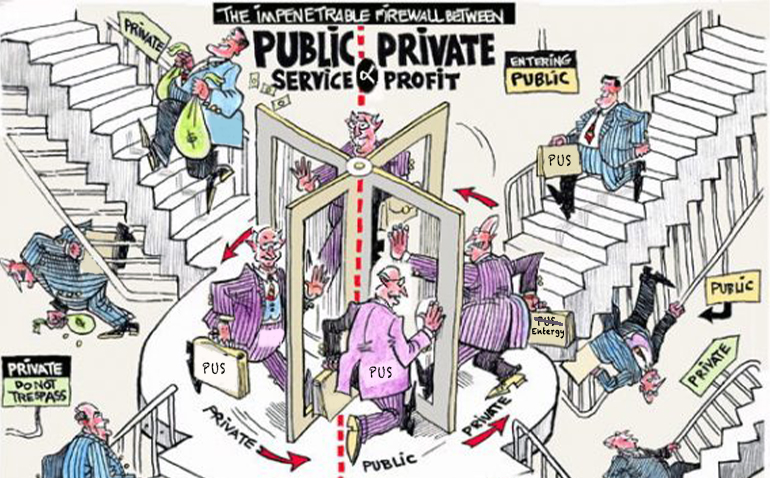

It is common for states to prohibit government employees from leaving a regulating agency to go to work for a company their agency regulated. Such “revolving door” restrictions are intended to prevent the temptation for the employee to treat a company favorably in order to gain a position with that company later.

Mississippi only imposes that restriction in very limited circumstances. Our constitution prohibits former public officials, up to a year after they leave office, from having a direct or indirect financial interest in contracts with the state or with local governments that were approved when they were in office. A state law prohibits performing “any service for any person or business…in relation to any case, decision, proceeding or application with respect to which he was directly concerned or in which he personally participated.” That’s a permanent ban, but it is very narrowly defined.

However, there is at least one law that goes beyond those prohibitions.

Employees of the Public Service Commission (PSC), which regulates Entergy and Mississippi Power electric power companies as well as water systems and other utilities, have an additional restriction, but it’s not one you would expect. The same applies to the Public Utilities Staff (PUS), which assists the PSC in its regulatory functions but is a separate, independent agency.

Employees of each of these agencies are barred from leaving their agency and going to work, for at least a year, for… the other agency.

Strangely, these employees are free to (and do) leave their agencies and immediately go to work for the companies they helped regulate. But they are not allowed to go to work for their fellow regulatory agency.

In the last eight years, six senior management / staff employees with many years of experience have left these agencies and immediately joined a regulated company. This includes two general counsels, a division director, and three commission lead-staffers.

To be clear, this freedom to defect, so to speak, does not extend to the Public Service Commissioners or the two officials who must be confirmed by the Senate, namely, the Executive Secretary of the Commission and the Executive Director of the PUS. But the employees at both agencies who do have that freedom have a substantial amount of knowledge and influence, since they are the ones who do the investigations and provide advice to the commission on significant matters affecting the utilities and their bottom lines.

This article should not be construed as a challenge to the character or motivation of any former PSC or PUS employee who has made the move to a regulated company. But with the not-insignificant number of employees who have done so, it seems prudent to remove the opportunity for someone with such influence to show favoritism to a regulated company in hopes of obtaining that company’s favor and a well-paid position in the future.

Sign up for BPF’s latest news here.